MANAGEMENT AND RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES

The following listing of opportunities is not a formal management plan but a menu of ecologically-focused options to consider regarding ecological management actions in near, mid, and long term.

⮚ NNIS Plant Removal

⮚ Wetland/Seep Restoration

⮚ Oak-Hickory Forest Restoration

⮚ Meadow / Open Area Development For Wildflower, Pollinator, and Bird Habitat

⮚ Stream Restoration To Increase Water Retention and Native Plant / Wildlife Habitat

⮚ Rare Species Protection and Restoration

⮚ General And Species-Specific Wildlife Habitat Restoration and Enhancement

NNIS SPECES PLANT REMOVAL

Recommendation:

Continue kudzu removal and focus on forest-interior invasive species between July 1 and April 15 annually. Critical species to target are Multiflora Rose, Amur Honeysuckle, English Ivy, Periwinkle, Oriental Bittersweet, Privet, Burning Bush, Watercress, and Japanese Honeysuckle

In the past 25 years, NNIS species have been recognized as one of the most serious threats to native habitats and wildlife. Onsite NNIS species areis currently moderate, having been extremely high previously due to kudu. It also varies greatly by species (which are numerous). The most troubling species are Kudzu, Multiflora Rose, Privet, Burningbush, English Ivy.

Locations - Efforts to remove these species first in key habitats like stream corridors, seeps, and relict wetland / bottomland zones is recommended, followed by easily accessible areas along forest / pasture boundaries and pasture interiors.

Removal Methods - Most NNIS species removals onsite will be done manually (cutting / pulling) and this is an entirely natural and community-centric method of removing NNIS species. Still, consideration for strategic chemical treatments should be given to select problematic woody stems using a combination of “cut and spray” herbicide application and girdling (in select cases). Cut and spray consists of cutting plants at ground level and applying concentrated herbicide directly into the cut roots within 5 minutes of the cut. This method limits the herbicide to root systems where it is then broken down by bacteria over time.

Non-chemical, mechanical (cutting) controls will eventually extirpate plants but it must be pursued on schedule and it can take many years for some species because mature root-systems may continue to re-sprout for long periods of time. Last – many stems can be simply pulled up by the roots if they are sapling-sized and smaller.

Monitoring and Follow-up Treatment - Monitoring of sites following control actions is critical for permanent removals because plants can recover from root-sprouting, extensive seed-bank germination, and re-introduction by wildlife (especially for fruit-producing species like Multiflora Rose, Privet, Burningbush, and Amur Honeysuckle. Monitoring and follow-up controls should be conducted on a monthly basis following initial controls to curb regrowth.

WETLAND / SEEP RESTORATION

Recommendation:

Continued NNIS species removal, favoring and “release” of select native shrubs and herbs; install “debris-dams” below wetland and seep areas to help elevate the water table.

The Park harbors an excellent opportunity to restore wetlands (including the seep). These are currently the most intact and natural habitats onsite compared with meadows which are not naturally occurring in their current form (though many native species occur and can thrive there). The wetland habitat onsite is remarkably intact and very good quality for the area having likely been flooded, impounded, and damaged historically. The Seep habitat is more damaged from having a former springhouse foundation still visible at its head and being dominated by the introduced Watercress.

Continued NNIS removals are the greatest benefit to the wetland, and care should be taken to focus these activities between July 1 and April 15 (generally) to avoid felling songbird nests.

“Release” of select tree species is difficult in this area since the wetland is so small but, in some cases, select Red Maples or Tulip Poplars which dominate may be required to increase light to shrub and ground-layers. For larger diameter trees, the process is most easily performed by girdling trees and performing “cut and paint” herbicide application so that trees remain standing.

This should be carefully considered and care must be taken to ensure that non-target shrubs, wildflowers and ferns are not trampled in the process.

Within the seep region, it is recommended that the former spring-house foundation is removed and if possible, all Watercress is removed and replaced with native herbs, sedges, and/or rushes. The foundation would be best removed in late fall or early winter. Watercress can be removed as they begin to grow and germinate in spring and then again periodically through the growing season.

OAK-HICKORY FOREST RESTORATION

Recommendation:

Continued NNIS species removal, favoring and “release” of select native trees / shrubs, wildflowers and removal of trash & debris in the northern region

Much of the Oak-Hickory Forest in the northern and southeastern is relatively intact with mature, large diameter trees, a strong guild of native tree saplings and seedlings, and native plants. Aside from NNIS species removals, the following actions are suggested:

⮚ “release” and selection of native tree and shrub species within forested area via removal of competing common and “weedier” and/or most common stems like Red Maple, Tulip Poplar, and American Holly.

⮚ development of “course woody debris (CWD), i.e., standing and fallen woody debris that would naturally exist in a mature forest.

⮚ dividing and relocating native plants from onsite for abundant species that once occurred throughout but are limited by invasive plants or historical damage.

“Release” and Girdling / Felling: The first primary method for restoring forests is to “release” select formerly dominant, less-common native tree and shrub species via removal of competing common and “weedier” prolific stems. That is – girdling (as standing dead) for larger trees like Red Maple or Tulip Poplar that are crowding or shading native trees such as American Beech, Shingle Oak, Black Cherry, Black Walnut, Northern Red Oak, Hickories (etc) in order for these trees to grow more rapidly and reach the forest canopy and recover.

This process can be applied to shrub species as well, particularly those which are larger and taller and which will then produce fruit and seeds more rapidly with greater sunlight access. This is best performed between mid-August (when migrator bat pups can fly) and mid-April before songbirds have set up nests that can be felled.

Development of “Coarse Woody Debris”: Coarse woody debris (CWD) consists of standing and fallen woody debris that would naturally exist in mature forests. CWD is a primary vector of topsoil formation, water retention, bat and songbird roosting, habitat for amphibians and small mammals, and critical fungal-network hotspots. This key feature can be encouraged by protecting existing CWD that are not threatening adjacent structures and properties and creating more CWD by girdling and/or felling select trees especially those that are very common (like poplar, red maple, or white pine) where other more favorable trees like Black Walnut, Willow Oak, Northern Red Oak (etc) that are diminished in number can thrive.

Retention of standing woody debris enables vast numbers of roosting sites for birds, small mammals and even amphibians throughout the year. Historical timbering, grazing and haying have all impacted these zones, but high numbers of large-diameter Sweetgum, Tulip Poplar, Red Maple, and Loblolly Pine occur that can easily be girdled or felled to allow other less common hardwoods to emerge into the canopy quickly.

Native Plant Division, Relocating and Reintroduction: This largely refers to dividing and transplanting native wildflowers and ferns within the site and/or reintroducing species that likely once occurred but were not observed. A listing of these species is shown below featuring native plants that occur onsite first followed by native plants that can be reintroduced into native forests easily.

For spring-flowering species, division is performed in mid-summer when plants begin to spot or yellow up (before they senesce). Clusters of plants like Christmas Fern or Jack-in-the-Pulpit are dug up, roots are divided, the original “mother” or largest root is placed directly back into the original location and offshoot roots are planted in both scattered locations that disperse them throughout the habitat type, but also in clusters of at least three roots per plant so the root systems can graft & share nutrients as they mature, which provides more resistance for the species.

For fall-flowering plants and most ferns - these are usually moved during early spring before they get too tall or Autumn after they’ve browned up.

Seed for sedges and grasses (which are abundant in Alluvial Forests) seed can be collected once the perigynia or spikelets (seed heads) are browning, then distributed in open areas in similar positions lacking those species.

MEADOW DEVELOPMENT FOR WILDFLOWERS, POLLINATORS and WILDLIFE

Recommendation:

Select for recovering native full-sun fruit-producing shrubs, wildflowers and sedges/rushes/grasses within open area recovery.

Though open, full sun meadow-habitat comprises approximately 30-40% of the property, native full-sun plant and wildlife habitat is only fair (but improving rapidly) due to kudzu invasion. Thus, meadow development in some form is recommended to provide full sun habitat for flowering, pollinator, bird, and other wildlife habitat that forests do not provide. This can include native tree, shrub, wildflowers and grasses / sedges/rushes that will provide food, cover, flowers / nectar, perching sites and greater niche-space for wildlife as well as species richness. These areas can be rapidly developed, even in the growing season of this survey.

Meadows provide exceptional habitat for open-area dependent songbirds, small mammals and their predators, pollinators, and high numbers of full-sun native wildflowers that pastures do not. When developed as “low” or “high” meadows and left to overwinter (which is crucial), these areas provide incredible year-round habitat that pastures and even forests do not.

Combined with wide, mowed trails for access, meadows can define one-of-a-kind walking and exploration opportunities with great views and exciting wildflower and wildlife interactions. Meadows are also the only habitats capable of supporting some species like Bluebirds, Tree Swallows, numerous Sparrows and many other birds requiring breeding and forage higher than ground level.

A rapid summary of the meadow development process is:

⮚ Plan meadow zones with and around mowed trail access in flat to gentle, accessible zones that can be bushhogged 1-2x annually.

⮚ Mow the perimeter of northern and southern Meadows at the forest interface and then one or two meandering trails in the meadow interior. This defines the meadow, helps prevent tree encroachment and is excellent for edge-wildlife species.

⮚ Allow native plants to grow and “reveal” themselves first without tilling or seeding.

⮚ Installation of native plants by rootstocks rather than seeds is suggested at first for species like milkweeds, petunia, native sunflowers, asters, blazing star and others near edges and closer to the house[1] (to view and water) if desired - see links below. Installation of root-stocks is more immediate compared to seed.

⮚ Addition of native fruit and nut producing shrubs (see below).

⮚ “Low” meadows are developed by mowing twice annually: once after July 1-7th (which allows meadow / ground-nesting bird fledglings to survive) and a second time from late-Feb to mid-March which removes woody vegetation.

⮚ “High” meadows are developed by mowing only once annually from late Feb to mid-March as new growth begins.

⮚ Allow low and high meadows to “overwinter” as intact above-ground cover. This is crucial winter cover for wildlife protection, forage, and escape cover, and erosion control and temperature amelioration in winter.

⮚ Pending results of initial meadow “release”, consider planting perennial rootstocks and native seed mixtures into open / exposed soil areas. Tilling is not recommended as weedier species can then dominate due to exposed soils.

Wildflower seed mixtures available online that will should thrive on Fox Creek are listed in Appendix B and can be purchased individually or in mixes like the following:

⮚ https://www.ernstseed.com/product/nc-piedmont-upl-meadow-mix/?anchor=130

Native shrubs that would thrive throughout the meadow and provide fruit for wildlife already exist and are modeled onsite including Cherryleaf Viburnum, Winterberry, Swamp Rose, Alternate-leaf Dogwood, Redbud, Blackberry, and native Hazelnuts.

STREAM RESTORATION

Recommendation:

Continued invasive species removal, native plant restoration and debris dam installation within streams to create riffle-pool, step-pool, and cascade elements; elevate a test debris dam below the wetland to test wetland and water table expansion there.

Like wetland and seep habitats, streams have been damaged but are in worse condition due to their deeply incised (cut downward) structure. This is due to sediment infill of the greater pond area and ensuing stream-based incision downward into the sediment, which has artificially lowered the stream basin. Using similar NNIS removal and native plant favoring and installation techniques as noted above. However, buffering on the western unnamed tributary would yield different restoration targets including Rich Cove Forest and Rich Montane Seeps, and typical upland stream conditions.

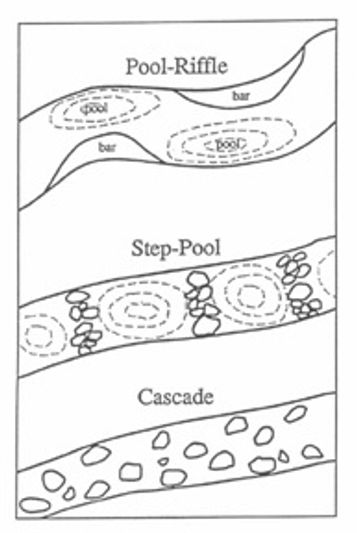

In-Stream Debris-Dams – the natural physical structure of creeks in the Fox Creek slope-range are “step-pool” and “cascade” channels (image left).

In step-pool channels, “steps” formed of woody debris, cobbles, and boulders alternate with finer materials in pools to form a rhythmic, staircase-like longitudinal profile. These step-pools self-organize over time until reaching a geometry that dissipates energy the most efficiently for the size of the sediments in the channel. Unusually high flow events destroy and re-form step-pool structures. Following such events, the channel bed gradually reorganizes itself into steps and pools. In its natural state, Fox Creek would support step-pool structure. In the northern Fox Creek stretch, pool-riffle complexes are attempting to form but are somewhat inhibited by channel incision.

Human-created debris-dams directly imitate natural accumulations in streams consisting of adjacent large-tree trunks and root-balls, crowns, limbs, branches, rocks and cobbles / sediments that naturally pile up behind these features. When these develop and elevate the stream basin, the debris begins to pile up against embankments to protect them, elevate the water

table, and begin restoring “riffle-pool”, “step-pool” and “cascade” sequences which define linear stream systems.

In Fox Creek Park, debris dams are recommended for installation in at least two test-locations: one on Fox Creek and one below the wetland to check feasibility. These can be initiated by installing several 6-8-foot lengths of 10-12-inch diameter trees or rock dams (if enough material exists). Common trees like Tulip Poplar, Red Maple or others that are proximate to the creek are ideal, taking care to avoid felling trees that have active bird nest cavities.

At each site, take care to gradually elevate only 12-15 inches per installation to ensure that existing cobbles (where all stream invertebrates live) are not flooded and will have time to migrate and re-form in new cobbles formed by the debris dam. This is likely more of an issue on Fox Creek than the wetland channel.

Embankment protection – Due to deep incisions from stormwater events and flooding, streambanks are excessively steep, undercut, and eroding in many locations. This is difficult to repair without having machines excavate the banks back to more sustainable slopes (expensive and requires permitting). But in addition to elevating the stream substrate, ongoing Kudzu removal can allow native plants to respond.

Example of in-stream debris dam recently developed in Yancey County

WILDLIFE HABITAT RESTORATION and ENHANCEMENT

Recommendation:

Preclude vegetation felling and clearing in forests and select open areas between April 15-June 30th, and avoid felling large diameter trees through Aug 15; add circular or linear debris piles; install additional Bluebird boxes and Martin houses

Songbird and Bat Protections

One of the easiest and most critical activities that help protect songbirds – the most important of which are tropical species that fly to North America to breed in forests annually - is to avoid clearing forest vegetation entirely between April 15–June 30th(the peak-breeding season for neotropical migratory songbirds).

If possible, extending this period to Aug 15 (at least for large diameter trees with flaking bark and standing dead trees) annually will provide protections for tree-roosting bats and bat-pups which can be prolific on older dead trees with flaking bark or live trees with naturally flaking bark like White Oak, Hickory, Sycamore and/or Red Maple. Felling and vegetation clearing avoidance in this time prevents dropping nests and egg clutches and bat-pups during the peak breeding season for species that are facing population declines.

Whereas “resident” (non-migratory) songbirds can produce numerous nests and chicks per year, neotropical migratory songbirds must fly thousands of miles from the tropics and back annually to nest in their home territories. Thus, they can produce only one and sometimes two broods of chicks per season before returning to the tropics for fall and winter – far less production than resident birds. Thus, clearing of forests and vegetation during their breeding season is partially a cause of their decline.

Bats, primary pollinators and insect removal machines are tree-roosting species onsite. Maintain all potential bat roosting sites in white oak trees (upper bark plates), Sycamore, Red Maple, and other bark-flaking trees where bats will roost and breed en-masse. Most bat species in the state are now federally listed, and their populations continue to plummet due to white-nose syndrome. Bats also help control insects, especially mosquitos; thus, higher bat populations mean greater insect removal.

If meadow-restoration is sought, allowing meadows to rest between April 15-July 7hallows open-area ground nesting and low-shrub nesting species to fledge their young without damage, after which strategic vegetation mowing can help enhance these areas.

Woody Debris Pilings

Consider installation of circular (pile) or linear (windrow) debris piles using woody material from fallen trees and NNIS species removals. Such pilings are excellent wildlife attractants year-round, drawing birds, small mammals and amphibians. They serve as nesting, feeding,” wintering” and escape-cover sites, can help retain notable amounts of water, and they break down over time tofor form rich topsoil. They are best located in places where plants are sparse and the are best scattered strategically vs. concentrated in a small area.

Bird-box Installation

Meadows onsite are excellent places to locate Bluebird (already onsite) and Purple Martin houses. Neither species are currently threatened or endangered, but both offer excellent bird-watching opportunities (especially near structures) and the latter offer excellent insect controls, aerial antics, and excellent watching.

Bluebirds - Though a single Bluebird box has been installed at the southwestern corner, consider installation of a second box in the northern meadow. Additionally, installation of two boxes with 15-20 feet of each other will allow the more aggressive Tree Swallows to take the other box. Swallows then prevent other Swallows from taking the 2ndbox, allowing Bluebirds to keep the box without competition since both birds are just about the same size.

Purple Martins - nest in gregarious colonies (often gourds or large houses) and east of the Rockies, have no naturally occurring nesting sites aside from Martin houses provided by humans. Martins (which are Swallows) typically nest in creek and river-bottoms with openings but would likely thrive in the central location of Fox Creek given the water resources onsite and proximity to the Swannanoa River. These birds are excellent aerialists, fun to watch for hours on end and provide major insect controls. Resources on Purple Martins can be found here: https://www.purplemartin.org/purple-martins